Adapt & Overcome: Considering Control Module Adaptation During Diagnosis & Repair

Brian Wing

History is brimming with examples of people overcoming obstacles and reaching goals by altering the way they attack different problems. In baseball, hitters who can adjust to different pitching styles will consistently get more hits and help advance the base runners. On the battlefield, soldiers achieve their objectives and live to fight another day by adapting to events as they unfold; for them, failure to adapt can have serious consequences.

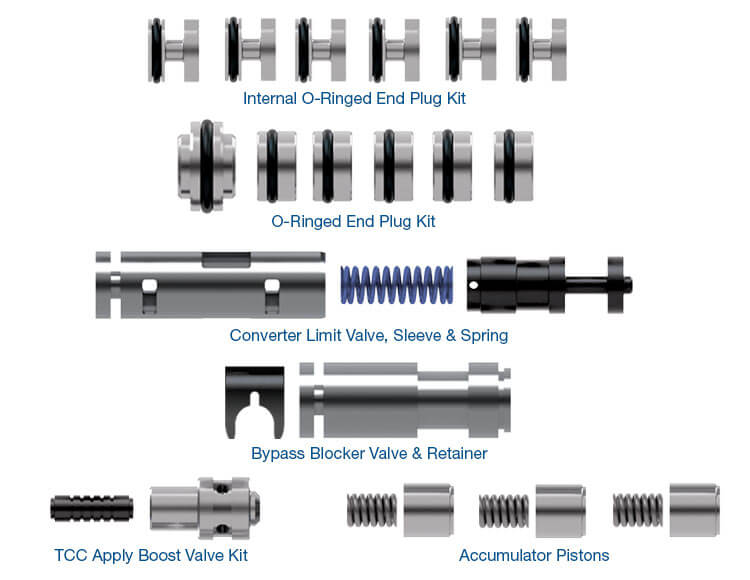

Transmission repair is no exception. Builders have become versatile in making mechanical modifications that restore OE operation or fend off common problems before they happen, from installing oversized valves to reinforcing drum splines to altering feed circuits.

But many technicians are unfamiliar with adaptive strategies that are part of the control mapping of the transmission control module (TCM) or powertrain control module (PCM). Failure to consider these adaptations can lead to unnecessary part replacement, never-leaves or comebacks.

What is TCM Adaptation?

The TCM is responsible for monitoring and controlling transmission operation through the use of various sensors, solenoids, relays, switches etc. Computer management provides benefits such as precise shift timing, fault detection and increased fuel economy. But a more remarkable feature is the TCM’s ability to compensate for changes—in engine performance, vehicle load, driving patterns, and physical wear inside the transmission—by adapting its control tactics.

Pressure regulator valves provide a good example of adaptation in action. These valves are relentlessly active, causing the valve and bore to deteriorate over time. This wear creates a path for fluid to escape the circuit, lowering (or raising) line pressure.

Using various sensors and calculations, the TCM “realizes” line pressure has strayed from specification and modifies the pulse-width signal to the pressure control solenoid, stroking the valve a little further to raise (or lower) pressure to compensate. This principle is in effect for all regulator valves, not just the main PR.

|

It doesn’t end with regulator valves. As bands and clutches degenerate, they take longer to apply when commanded. The TCM “notices” this and adjusts apply and release timing to maintain shift quality. In fact, there is constant monitoring and manipulation of components taking place throughout the transmission at all times. Adapting in this manner allows the TCM to provide normal operation and shift feel even as various components age and wear.

But adaptation cannot hold wear at bay forever. Eventually wear overcomes the TCM’s ability to compensate and becomes apparent to the driver in the form of harsh or soft shifting, delayed engagement and shift timing problems. When the TCM reaches the limit of its adaptation window, trouble codes will be triggered, such as GM’s “Maximum Shift Adapt” code P1811.

Adaptation can coax thousands of extra miles out of the transmission, but wear often progresses to the point where repair or rebuild is necessary.

After the Build

Common tech support calls after rebuild concern problems that weren’t there before the build:

- “There was a flare before the build. Now the flare is gone, but there is a bind and all shifts are harsh.”

- “There were temperature-related problems before we replaced solenoids. That went away, but now the shift timing is off.”

- “Before, we had no lockup. Now we have harsh lockup.”

Usually the technician suspects there is a self-inflicted wound, additional components requiring replacement or that the original diagnosis was wrong. While this could be the case, these are problems that are also commonly caused by failure to reset adaptations after repairs are performed.

Back to the pressure regulator example: If adaptations have evolved to raise pressure in compensation for a worn valve and you fix the problem, the TCM must be “informed” of the repair by resetting adaptations. Otherwise the TCM will continue controlling the transmission as though it contained a worn valve, resulting in excessive pressure and harsh shifting.

Do Not Tempt the Gods

At this point, you might be thinking about skipping the reset process. After all, it has just been established that the TCM will adapt on its own—why not simply let it “do its thing”?

Remember that adaptation consists of small, incremental control changes in response to gradual component wear. During repair or rebuild, worn parts are instantly eliminated. It takes time for the TCM to adapt to change that radical, during which serious damage can be inflicted on the transmission. Preventing a post-build grenade from going off inside the case is a compelling reason to reset adaptations on all units that have a reset procedure.

Resetting Adaptations

Contrary to popular belief, adaptations are not reset when trouble codes are cleared. Each manufacturer has their own reset or “relearn” procedure to follow. Some OEMs have different methods from model to model. Some—such as the majority of BMWs—are easy: use a capable scan tool and click on “Reset Adaptations.”

Some are a bit more involved. Many Audi/VW models require using a scan tool in combination with shifting through gears a number of times during a test drive. Other manufacturers have similar shift progression reset schemes. Some require a simple battery reset. Some models have no reset procedure at all, adapting to new parts automatically after relatively short drive cycles.

It is important to check manufacturer-specific reference material to determine the reset procedure for the vehicle model being worked on. Notice that says vehicle model, not transmission model. This is because some transmissions—such as Aisin AW 55-50SN—are installed in a range of vehicles containing different control units. The reset procedure for a Volvo will not be the same as that for a Chevy.

Adaptations vs. Reflash

There is often confusion between resetting adaptations and reflashing the control unit. When discussing adaptation reset, it is common to hear a technician say something like “We checked with the dealer and they said it does not need a reflash.”

It must be stated that resetting control unit adaptations and reflashing the control unit are two distinctly separate procedures with different purposes:

- Reflashing involves changing the control software in the TCM. This software comprises the instructions that command the TCM how to operate the transmission. Anytime there is a need to change a control parameter, revised software is uploaded to the TCM in a reflash.

- Resetting adaptations is simply directing the TCM to return to its baseline control setting, where adaptation will begin anew for the freshly installed parts. There is no software change involved.

Everyone Gets Home Safely

Resetting adaptations is mandatory for many electronically-controlled transmissions, and the future holds more of the same. Including adaptation reset in your build routine is essential to guarantee a complete, dependable repair. Your ability to adapt will help get your customers where they need to go, without stranding runners on base or leaving soldiers behind.

Related Units

Related Parts

While Sonnax makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of technical articles at time of publication, we assume no liability for inaccuracies or for information which may become outdated or obsolete over time.